The Act was considered by Catholics as a usurpation of papal authority. Meanwhile, relations with the regime of Elizabeth I of England continued to deteriorate, following her restoration of royal supremacy over the Church of England through the Act of Supremacy in 1559 this had been first instituted by her father Henry VIII and rescinded by her sister Mary I, Philip's wife. As a defender of the Catholic Church, he sought to suppress the rising Protestant movement in his territories, which eventually exploded into open rebellion in 1566. In the 1560s, Philip II of Spain was faced with increasing religious disturbances as Protestantism gained adherents in his domains in the Low Countries.

In the treaty, England and Spain agreed to cease their military interventions in the Spanish Netherlands and Ireland, respectively, and the English ended their high seas privateering.

It was brought to an end with the Treaty of London (1604), negotiated between Philip III of Spain and the new king of England, James I. The war became deadlocked around the turn of the 17th century during campaigns in the Netherlands, France, and Ireland.

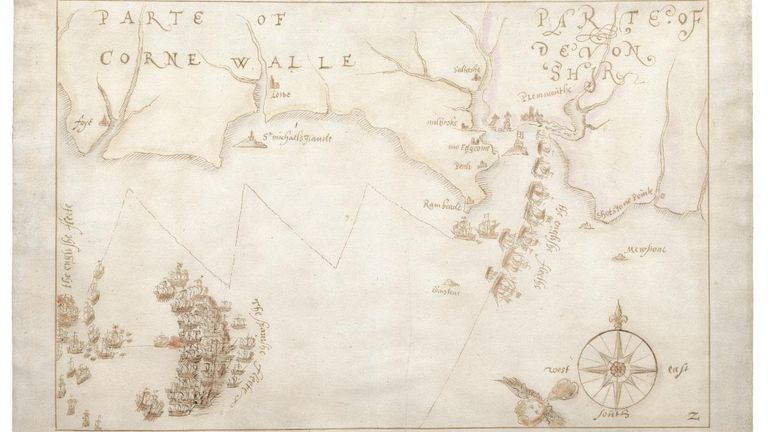

Three further Spanish armadas were sent against England and Ireland in 1596, 1597, and 1601, but these likewise ended in failure for Spain, mainly because of adverse weather. The English enjoyed a victory at Cádiz in 1587, and repelled the Spanish Armada in 1588, but then suffered heavy setbacks: the English Armada (1589), the Drake–Hawkins expedition (1595), and the Essex–Raleigh expedition (1597). It began with England's military expedition in 1585 to what was then the Spanish Netherlands under the command of the Earl of Leicester, in support of the Dutch rebellion against Spanish Habsburg rule. The war included much English privateering against Spanish ships, and several widely separated battles. The Anglo-Spanish War (1585–1604) was an intermittent conflict between the Habsburg Kingdom of Spain and the Kingdom of England.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)